While most Americans spent the 1st week of December picking out a Christmas tree, James spent his at a conference in Benin, kicking-off West African Food Security Partnership. Long story short: Peace Corps is partnering with USAID (the US development agency) to bring together food security programs in the ten West African countries where Peace Corps is active. Since Peace Corps staff was brought in from all of these countries, it was a great opportunity to collaborate on strategies and resources-used to improve food security in our respective countries.

But since hearing about Benin itself is probably more interesting to our blog readers, I’ll start there. Though they kept us busy, I found some time to explore Benin with the help of some volunteers from Peace Corps Benin. While our countries are in the same region, we were surprised to learn that our experiences are very different. First of all, southern Benin is tropical, more developed, and has greater access to diverse foods (including cheese!). Also, volunteers ride motorcycles, must live in concrete houses, and dance to salsa at night clubs. Yet ironically, they complain about these things while Mali volunteers – including myself – complain about dryness, bus transport, mudbrick houses, and Malian music! Oh humanity, thou art always discontented. But on the downside, volunteers said that city folk are more aggressive, and proximity to Nigeria means some sketchy neighborhoods. I also saw first-hand why Benin is known for Voodoo, which is not hidden like in other African countries; in a house we visited, a Voodoo fetish hangs next to a picture of Jesus. But of course, in my short time I only saw a fraction of the country.

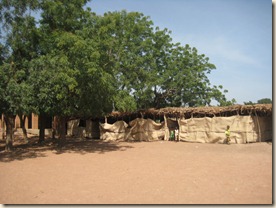

But I did not feel jipped – far from it. This was because I was very happy staying within the conference venue, the Songhaï Center and NOT just because I had a hotel room 3x the size of my mud-hut! This inspiring center (run by Father Godfrey, pictured below) is essentially a sustainable and organic farming community that strives to be a model for rural development in Africa. Just a walk through their garden gave me so many ideas for my work in Mali! And since we were staying on this working farm, we ate extremely well with meat, vegetables, and fruit juices that came directly from the grounds. We had quail eggs, turkey, and freshly squeezed pineapple juice – such a treat!

But fun aside, I honestly spent about twelve hours a day working on the Food Security conference. Being from Mali, I helped present (along with Mali’s food security program director Karim Sissoko, pictured with me below) some of our best practices and lessons learned from our current food security program. As one of two volunteers attending, I presented on strategies to get volunteers involved. Lastly, as an aspiring agricultural economist, I collaborated with a team to develop a plan for the program’s monitoring and evaluation. At the conference closing, we all received a certificate for our hard work from the PC Benin Country Director and US Ambassador to Benin, which I thought was a nice touch.

Along the way, I was also privileged to able to meet Peace Corps country directors and programming staff from Senegal, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Cape Verde (to name a few), all of whom had a wealth of knowledge and experience, but very different backgrounds and stories. My conversations with them were thought-provoking and inspirational, particularly as I consider my own future, and I hope to continue working with the Partnership from my post here in Mali. As I do, I will be sure to keep you updated with our activities, many of which are already underway.

Thanks for reading! -James